|

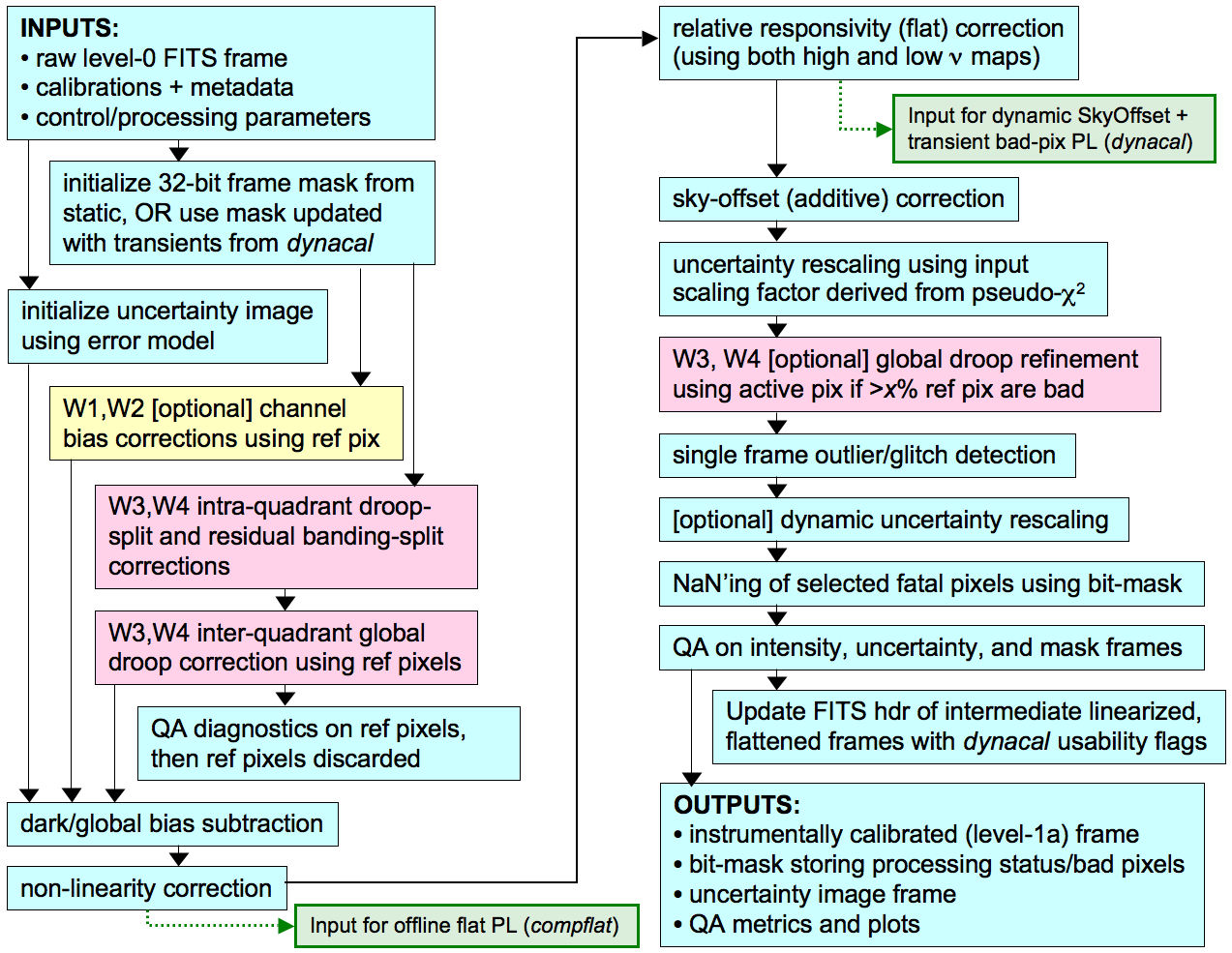

| Figure 1 - Processing flow in WISE instrumental calibration (ICal) pipeline. |

The purpose of instrumental calibration (ICal) is to read in a raw (Level-0 or L0) single exposure frame and correct it for instrumental signatures, e.g., dark current, non-uniform responsivity, non-linearity, and other detector-induced electronic signatures. Optical artifacts and signatures induced by telescope optics, e.g., ghosts, glints, global FOV distortion, PSF non-isoplanicity, including image persistence (latents) are not discussed here. These are covered in detail under the ARTID processing system. ICal also initiates pixel uncertainties for a frame using a noise model. These uncertainties are propagated and updating downstream as calibrations are applied. A bit-mask image is also initiated per frame and updated. This stores the status of processing on each pixel as well as prior knowledge of bad hardware pixels. The intent here is to summarize processing algorithms, how calibrations were made, and their overall performance.

The calibrations are band dependent and differ considerably between the HgCdTe arrays (serving W1, W2 at 3.4, 4.6μm respectively) and Si:As arrays (serving W3, W4 at 12.1, 22.2μm respectively). A description of the payload and detectors is given in section III.2. Details on pre-flight characterization and specific detector properties are given in Mainzer et al. 2008. It's important to note that the pre-flight (ground) calibrations differed significantly from those made using on-orbit data. This could be due to the different environment and/or electronics used in ground testing.

The ICal pipeline generates three (level-1b or L1b) FITS image products per band: the main calibrated intensity frame, accompanying uncertainty frame, and mask image. These are generically named: frameID-wBAND-int-1b.fits, frameID-wBAND-unc-1b.fits, and frameID-wBAND-msk-1b.fits respectively. The uncertainty image contains a 1-sigma error estimate in the intensity signal for every pixel and are used in generating the Atlas Image uncertainty maps. Quality Assurance (QA) metrics and plots are also generated for each frame. For details on frame QA, see section IV.6.b.ii.

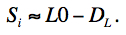

The pixel units of a raw input L0 frame are expected to be those as generated by the on-board Digital Electronics Box (DEB). The DEB (Data Number or DN) output is given by Eq. 1. It has the general form: a + b*slopefit, where slopefit is the fitted slope (or rate) to non-destructively read Sample-Up-the-Ramp (SUR) values generated by the Focal-plane Electronics Box (FEB), and a, b are constants. The pixel values in a calibrated intensity frame therefore scale as ∝ slopefit (or the photon accumulation rate), where the bias term a is implicitly removed by the dark subtraction step. A calibration factor (or equivalent photometric zero-point offset) is computed downstream in the WSDS pipeline using photometry relative to a standard star network (see section IV.3.g). This information is stored as the MAGZP keyword in the FITS headers of L1b products, and allows one to convert from DN to absolute flux units (e.g., see Eq. 1 in section IV.5.a.ii).

Figure 1 captures the major processing steps in ICal.

The cyan/bluish-colored boxes indicate steps generic to all bands.

The single yellow box is specific to W1 and W2, and the operation

therein was not performed in processing for the preliminary release.

Red is specific to W3 and W4.

Intermediate frame inputs for offline

flatfield creation (compflat),

and the dynamic sky-offset generation

pipeline (dynacal)

are shown in green.

|

| Figure 1 - Processing flow in WISE instrumental calibration (ICal) pipeline. |

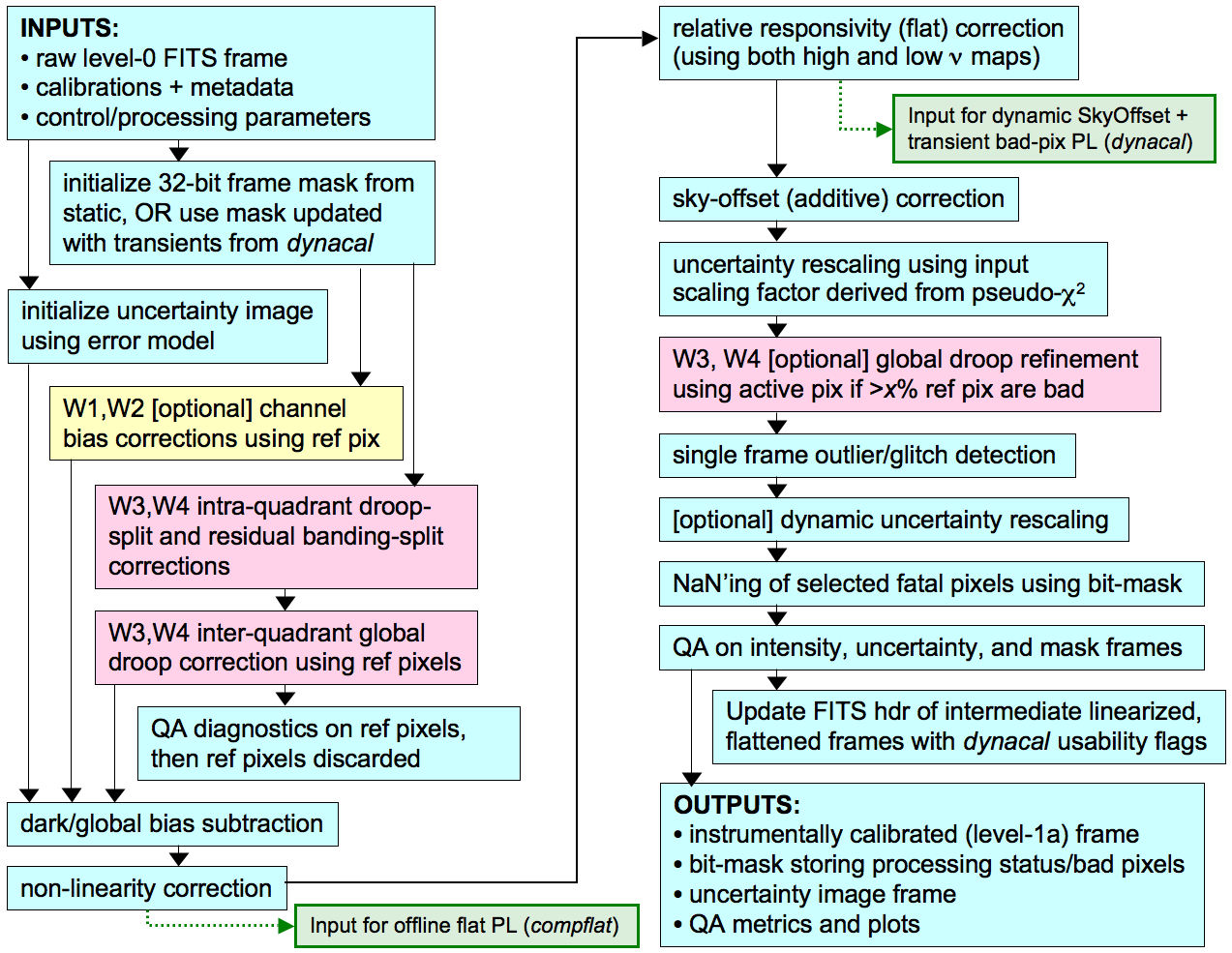

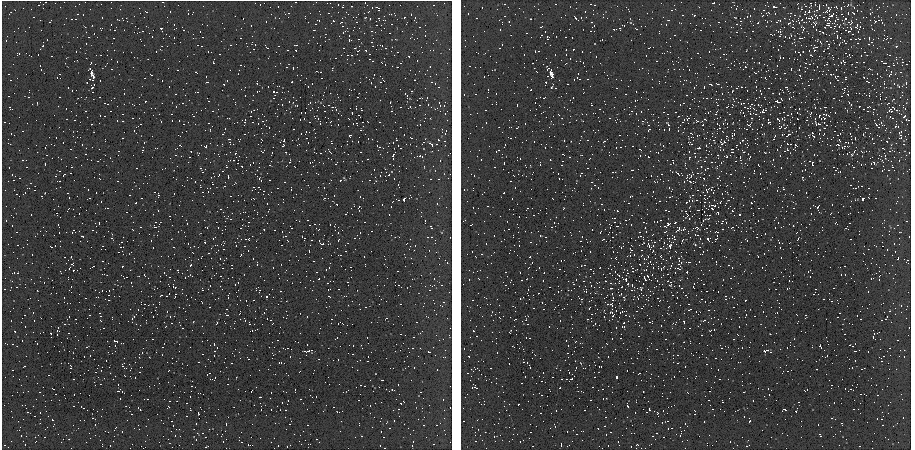

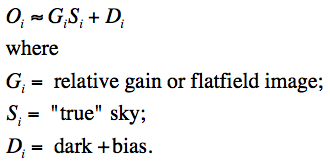

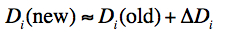

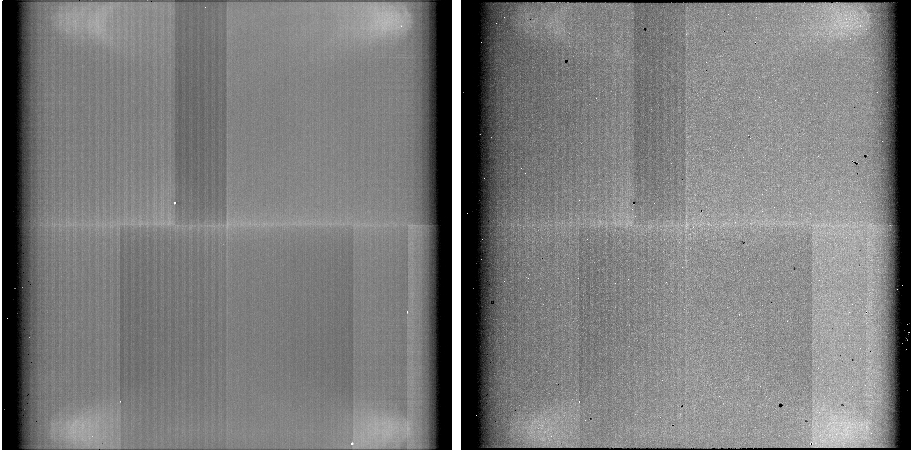

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 respectively show examples of W1 and W3

intensity frames processed at

various intermediate steps of the ICal pipeline.

Results for W2 and W4 are similar. The incremental

improvements are more easily noticeable in processing of the Si:As arrays

(W3 and W4), in particular in the droop

and sky-offset correction steps in

Figure 3.

The sky-offset correction has nicely removed the trail of

latent footprints in the bottom right of the frame.

|

| Figure 3 - Images of intermediate instrumental calibration steps for W3. Corresponding steps are shown in the box. Pixel signal is at same stretch in all images. Note: the final L1b frame with NaN'd pixels (like in Figure 2) is not shown here. W4 is similar. |

The pertinent detector calibrations are summarized in Table 1. Also shown is the origin of the data used to create the calibration product for each band ("ground", In-Orbit Checkout [IOC], and/or "survey"), and the format, i.e., whether the calibration was created for every frame pixel ("image"), or whether a single number was only possible. Static calibrations made from "survey" type inputs used data from the first six weeks of the science mission, i.e., what was available prior to commencement of first pass processing for the preliminary release. Sky-offset calibrations and transient bad-pixel masks were made dynamically (on a per frame basis) throughout the mission.

| Calibration | Origin of Input Data | Format |

|---|---|---|

| darks | W1,W2: IOC cover-on

W3,W4: survey (in conjunction with flats) |

image |

| non-linearity | ground with IOC check | image |

| relative responsivity (flats) | survey | image |

| low spatial frequency flats (not applied; only sanity check) | survey: from relative source photometry | image |

| sky-offset correction | survey: derived dynamically per frame | image |

| electronic gain [e-/DN measures] |

survey | single number per band |

| read-noise sigma per pixel | IOC cover-on, then rescaled using single number survey estimates | image |

| static bad-pixel masks | made using all calibrations | image |

| masks of bad-pixel transients | survey: derived dynamically per frame | image |

| droop parameters (W3,W4 only) | survey: reference pixel baselines | single numbers (four per band) |

The frame mask is a 32-bit image product (generic name frameID-wBAND-msk-1b.fits) that stores pixel status information for its corresponding single exposure intensity frame (frameID-wBAND-int-1b.fits). It stores both "static" information on bad-hardware pixels (replicated from the static calibration masks), and dynamic information on which pixels became saturated and transiently bad, and any hiccups/warnings in the application of calibrations during ICal processing. The mask is initialized and updated in the ICal pipeline (see section iii.) and further updated downstream during co-addition in the outlier detection step. The primary purpose of the frame mask is for omitting bad and outlying pixels from co-addition during Atlas Image generation.

The pixels in the frame mask are represented as 32-bit signed integers (FITS keyword BITPIX = 32) with certain conditions assigned to the individual bits. Useable bits are numbered from zero (the Least Significant Bit [LSB]) to 30. The sign bit, bit 31, is not used. If the bit has the value 1, the condition is in effect. Zero implies that the condition is not in effect. Pixel values in a mask can certainly encode a combination of bits, and no attempt was made to keep the bit assignments mutually exclusive. For example, a mask pixel value of 10485832 encodes bits 3, 6, 23 and 21, i.e., 10485832 = 23 + 26 + 223 + 221.

The conditions assigned to each bit, where available, are defined in Table 2. Note: these definitions only pertain to frame products from the preliminary release. Bits are redefined in final-release products.

| Bit# | Condition |

|---|---|

| 0 | from static mask: excessively noisy due to high dark current |

| 1 | from static mask: excessive read noise not due to high dark current |

| 2 | from static mask: dead or very low responsivity |

| 3 | from static mask: low responsivity |

| 4 | from static mask: high responsivity |

| 5 | from static mask: saturated anywhere in ramp |

| 6 | from static mask: high, uncertain, or unreliable non-linearity |

| 7 | from static mask: broken pixel or negative SUR (raw frame down-linked value = 32767) |

| 8 | reserved |

| 9 | broken pixel or intrinsically -'ve SUR (downlink value = 32767) |

| 10 | saturated in sample read 1 (down-link value = 32753) |

| 11 | saturated in sample read 2 (down-link value = 32754) |

| 12 | saturated in sample read 3 (down-link value = 32755) |

| 13 | saturated in sample read 4 (down-link value = 32756) |

| 14 | saturated in sample read 5 (down-link value = 32757) |

| 15 | saturated in sample read 6 (down-link value = 32758) |

| 16 | saturated in sample read 7 (down-link value = 32759) |

| 17 | saturated in sample read 8 (down-link value = 32760) |

| 18 | saturated in sample read 9 (down-link value = 32761) |

| 19 | reserved |

| 20 | reserved |

| 21 | new/transient bad pixel from dynamic masking |

| 22 | flat-fielding (responsivity correction) unreliable |

| 23 | sky-offset correction unreliable |

| 24 | reserved |

| 25 | contains probable latent flux |

| 26 | non-linearity correction unreliable |

| 27 | contains cosmic-ray or outlier that cannot be classified (from temporal outlier detection in multiframe pipeline) |

| 28 | contains positive or negative spike-outlier |

| 29 | reserved |

| 30 | reserved |

| 31 | not used: sign bit |

NaN'ing of bad frame pixels

The frame masks are used at the end of ICal processing to reset pixel values in the final calibrated intensity and uncertainty frame products to NaNs. Only pixels with specific fatal conditions are reset. The fatal conditions in Table 2 for NaN'ing frame pixels in the preliminary release are those defined by any of the following bits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, OR, 18. This applies to any band.

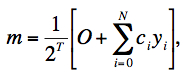

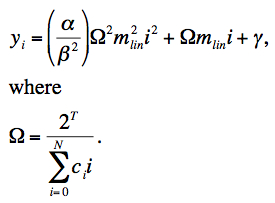

In general, the observed raw signal m per pixel is computed on-board from a linear combination of non-destructively read Samples Up the Ramp (SUR) yi:

|

(Eq. 1) |

where nominally N = 8; ci are the SUR weighting coefficients: {0,-7,-5,-3,-1,1,3,5,7} for W1 & W2, and {-4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4} for W3 & W4; O is an offset (= 1024 for all bands), and T is the number of LSB truncations, where T = 3, 3, 2, 2 for W1, W2, W3, W4 respectively. The time interval between the sample reads yi is 1.1 sec. This results in an effective pixel exposure time of 7.7 sec for W1, W2 and 8.8 sec for W3, W4. The shorter exposure time for W1, W2 is due to omission of an erratic first sample (with weight c0 = 0).

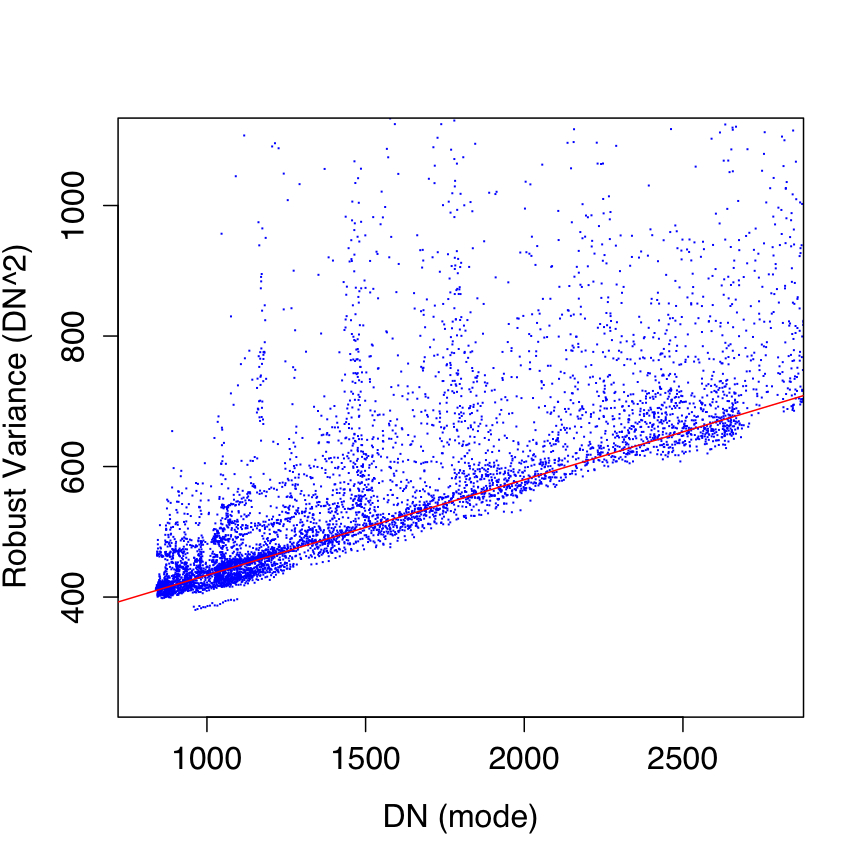

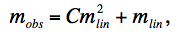

One-sigma uncertainties for each pixel in an input frame are initialized using a simple traditional Poisson + read-noise model. The noise-variance in a pixel signal m (in DN2) can be written:

|

(Eq. 2) |

g is the electronic gain in electrons/DN, and σ2RN is the read-noise variance in units of DN2. The bias term O/2T as defined above is removed before computing the Poisson noise component. The gain and read-noise terms were determined using on-orbit image data as described in section ii.1. The benefit of deriving these terms empirically is that certain multiplicative factors due to for example spatially correlated noise from pixel cross-talk and correlated noise between reads in the SUR technique (Eq. 1) can be absorbed into the parameter g (which no longer becomes a "true" electronic gain). As shown in section ii.1., we find that this method accurately predicts a posterior estimates of the pixel noise as measured from RMS fluctuations in the background. Also, the reduced χ2 metric from PSF-fit photometry to point sources, i.e., effectively the ratio: [variance in fit residuals]/[prior noise-variance propagated from Eq. 2 + other photometric noise terms] is on average ≈ 1. Note that PSF-fit photometry and other relevant noise terms (e.g., source confusion) are described in section IV.3.c.iii.

The uncertainty estimated from Eq. 2 was propagated and updated as each instrumental calibration step was applied, i.e., uncertainties in the calibration products were appropriately RSS'd with the frame-pixel uncertainties at each step of the pipeline. The calibration uncertainties only captured the random/statistical component, and amounted to no more than 0.5%. Systematic components characterized after processing and during QA (e.g., section x.) were not included.

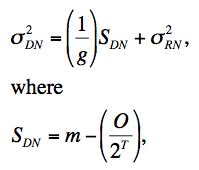

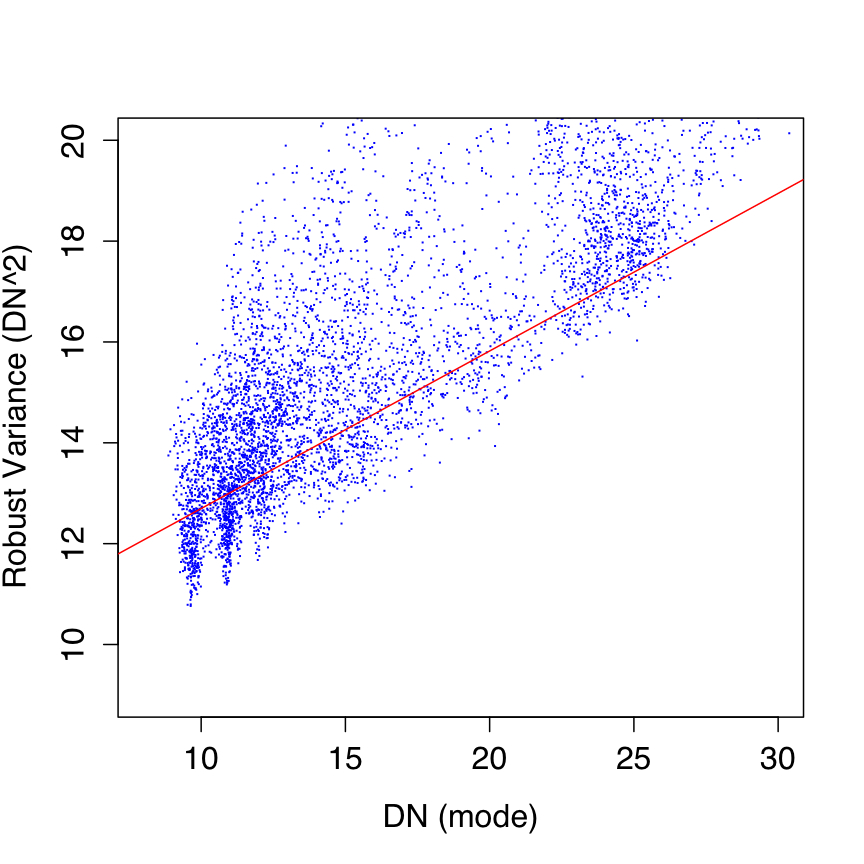

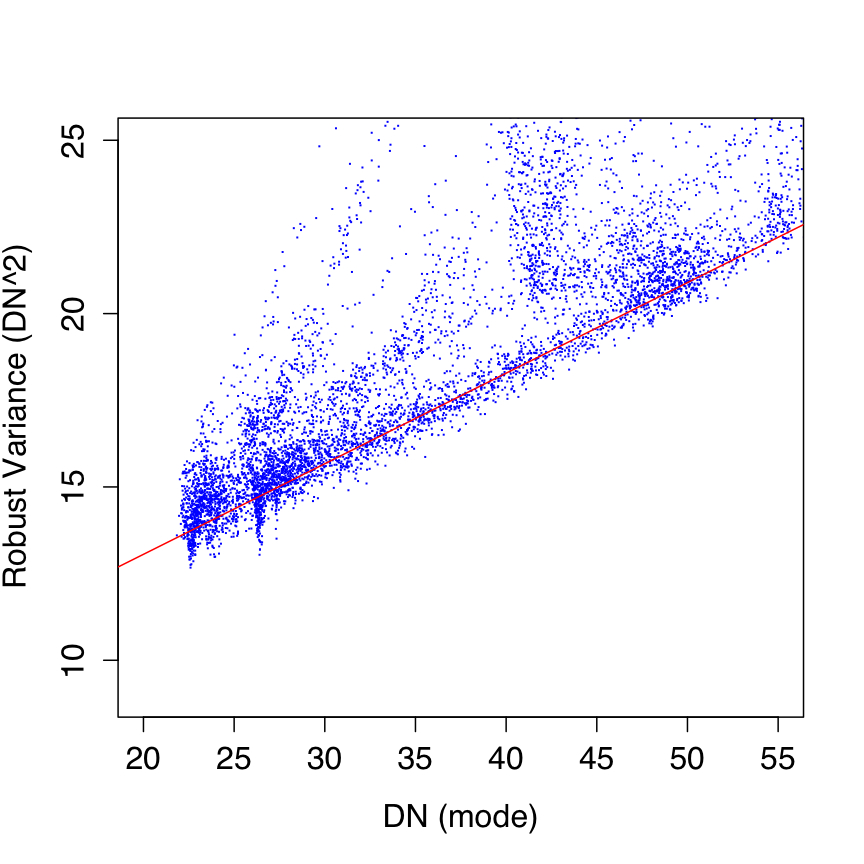

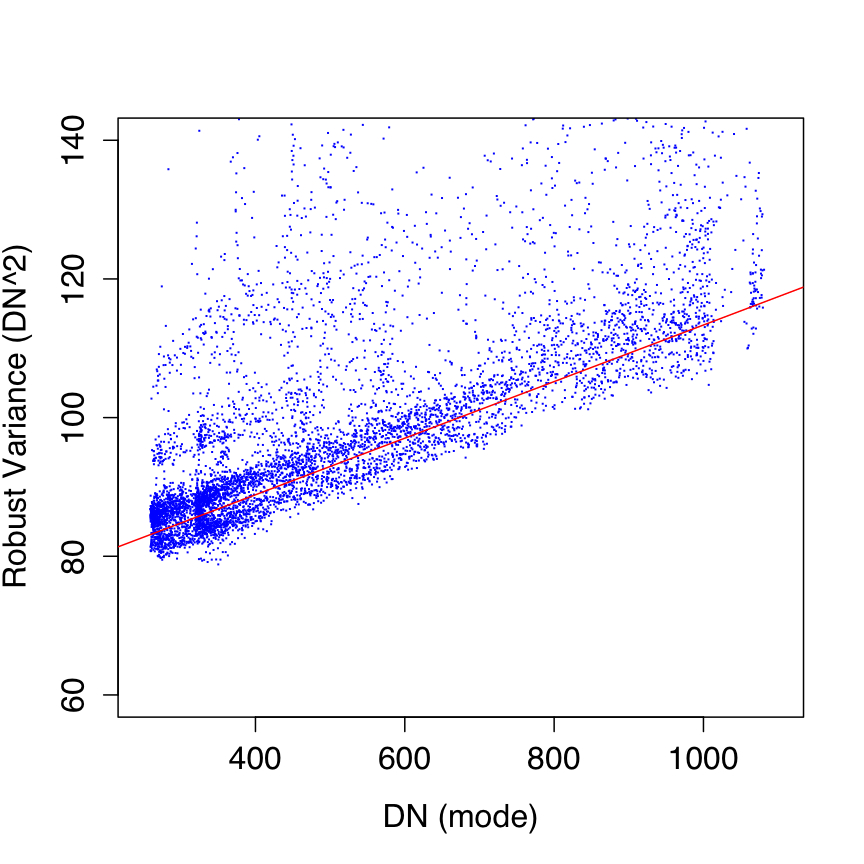

The effective gain and read-noise terms in Eq. 2 were estimated from on-orbit data by first computing robust measures of the spatial pixel variance (σ2DN) and modal signal (SDN) in ~7000 instrumentally calibrated frames spanning the full ecliptic latitude range. The robust variance metric used the lower-tail standard deviation from the pixel mode (with low-tail outliers trimmed). The spread in ecliptic latitude provided a varying background signal (and spatial variance) in all bands to allow a fit of Eq. 2 to measurements of σ2DN versus SDN. The slope from such a fit is then simply 1/g and the intercept is the read-noise variance σ2RN, the square root of which is the read-noise sigma sought for.

Even though robust metrics for the measurements were used, they were still affected by the inevitable presence of sources and structure in the background. We therefore performed the fitting of Eq. 2 using a robust linear regression method based on the concept of the M-estimator. Plots of fits to the data are shown in Figure 4 with parameter estimates for g and σRN given in columns 2 and 3 of Table 3. Our robust fits more-or-less spanned the lower envelope of the variance distribution at each modal signal level, i.e., that represented by the underlying background.

The above method yielded single estimates of the effective gain and read-noise for all pixels of a band in general. It would have been a tedious task to estimate these parameters for each pixel using the above method (e.g., by measuring instead the temporal stack variance versus signal level for each pixel). We therefore adopted the single gain estimates as listed in Table Table 3 for use in Eq. 2. For the read-noise however, we combined the single fitted values for σRN with read-noise maps derived from stacking cover-on dark data during IOC. The modes of these dark/read-noise maps are listed in column 4 of Table 3, and only W1 and W2 were reasonably close to our single parameter estimates. The discrepancy for W3 and W4 is described in note [2] of Table 3. In the end, we rescaled the dark/read-noise maps from IOC by the ratio: "fitted σRN"/"mode of IOC RN map" to arrive at read-noise maps for use in the pipeline.

|

|

|

|

| Figure 4 - Robust pixel variance versus modal pixel signal for W1, W2, W3, W4 (left - right). Red lines are robust fits of Eq. 2 with best fit parameters in Table 3. | |||

| Band | Gain[1] [e-/DN] |

Read-noise sigma[1] [DN/pixel] |

Read-noise from IOC dark data[2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.20 | 3.09 | 2.91 |

| 2 | 3.83 | 2.79 | 2.67 |

| 3 | 6.83 | 16.94 | 19.56 |

| 4 | 24.50 | 8.52 | 10.52 |

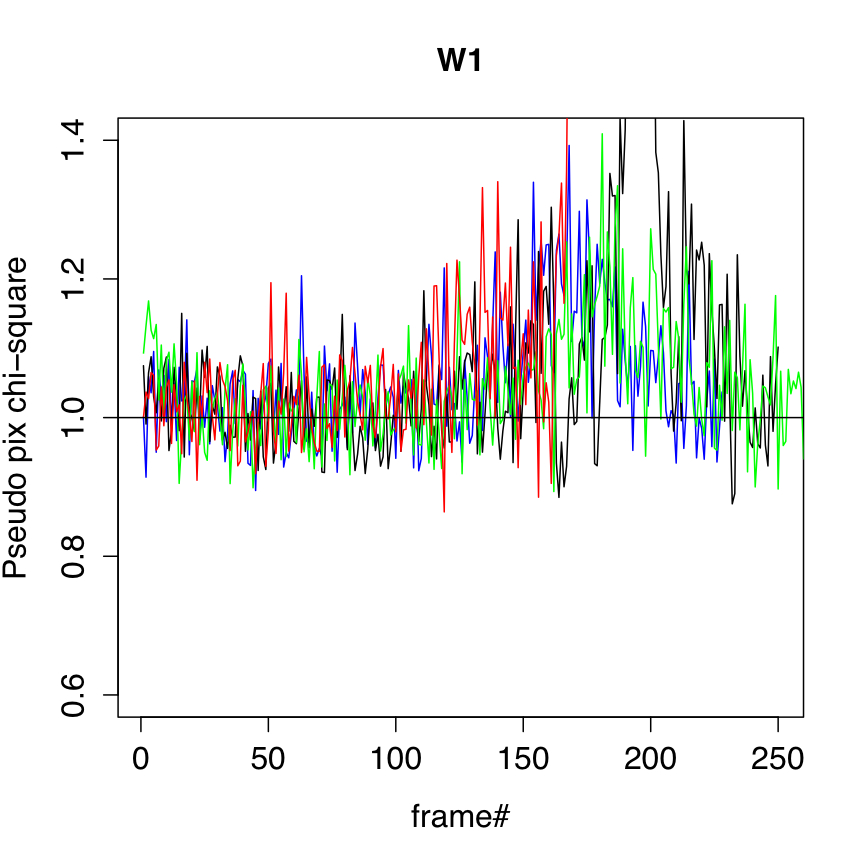

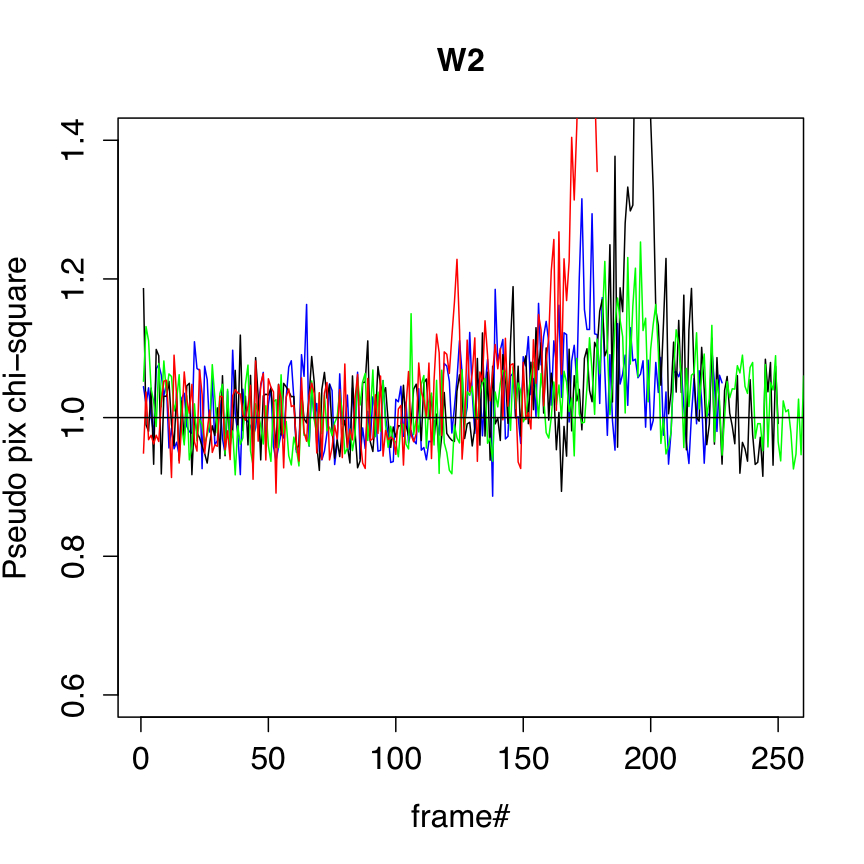

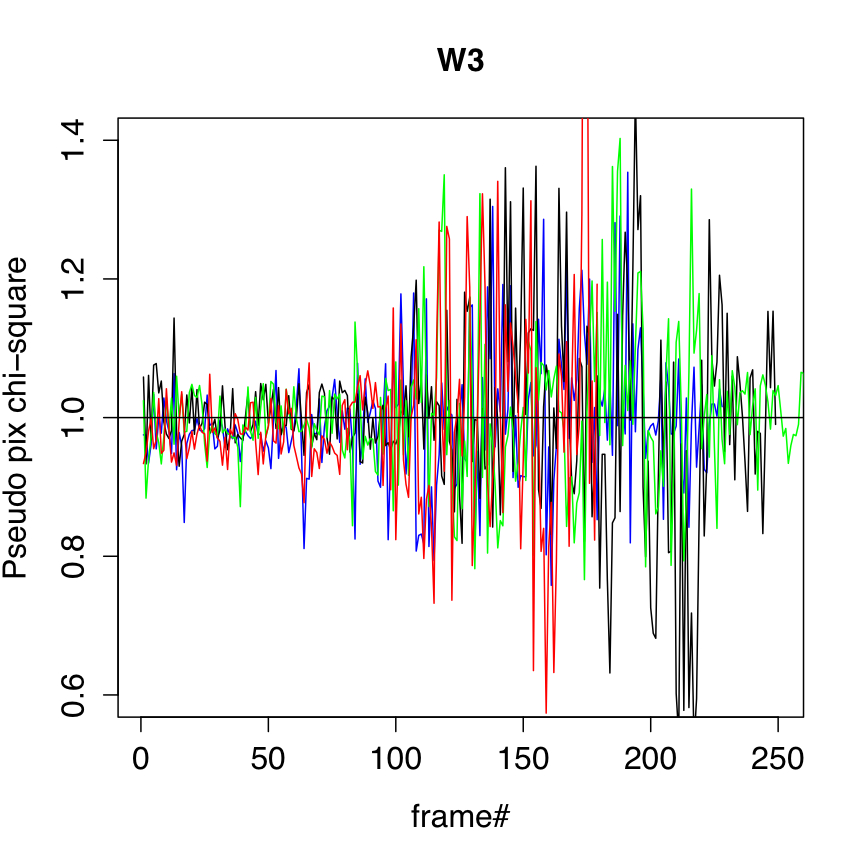

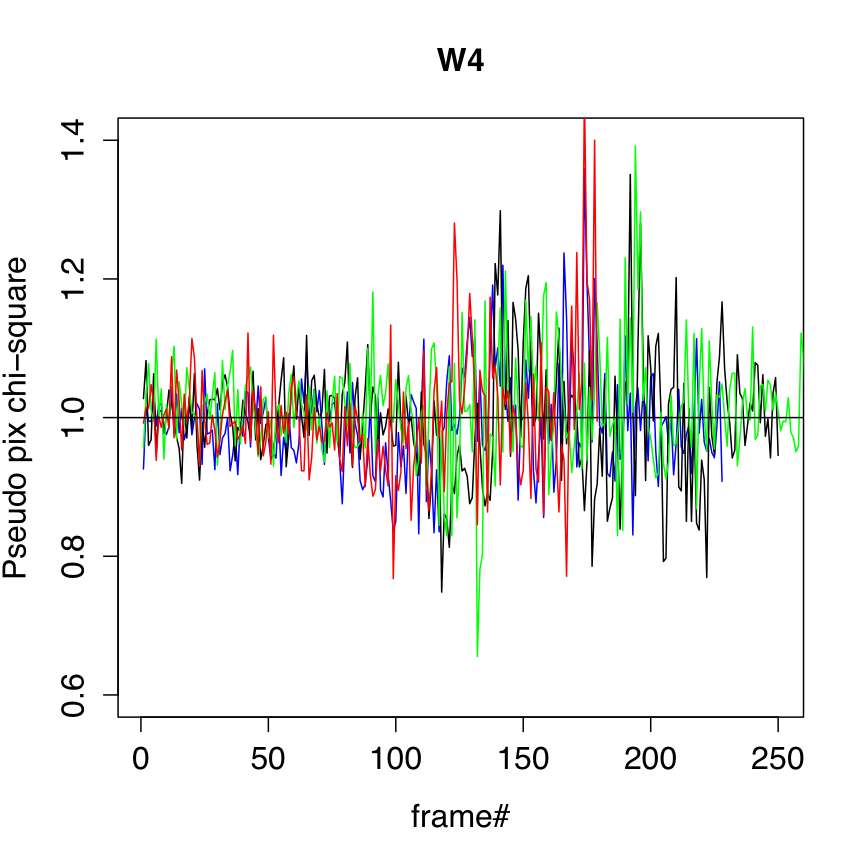

The uncertainty frame products were validated against measurements of the RMS fluctuation about the background in the corresponding intensity frames. We used an automated algorithm to select frame background regions that were ≈ spatially uniform and with low to moderately low source-density. A trimmed lower-tail standard deviation from the mode was used as a proxy for the RMS. This measure was divided by the modal pixel uncertainty over the same regions (as estimated and propagated from Eq. 2) to arrive at a pseudo reduced χ2 measure per pixel. This measure is shown as a function of frame number for four different survey scans in Figure 5. These scans came close to the galactic plane with the source density peaking at around frame number 180. Our robust RMS metric was not totally immune to the presence of astrophysical structure, and therefore exceeded the uncertainty model prediction at these locations.

Overall, the uncertainty model is seen to track noise fluctuations in the underlying background reasonably well, both in the read-noise limited W1, W2 bands, the quasi-readnoise limited W3 band, and the background-photon dominated W4 band. This holds all over the sky (setting aside contributions from source confusion) and throughout the duration of the crygenic mission. It is also encouraging that global analyses of PSF-fit photometry to point sources show reduced χ2 values of ≈ 1 on average for all bands (section IV.3.c.iii).

|

|

|

|

| Figure 5 - Ratio of "robust pixel RMS/model (modal) pixel uncertainty" versus frame# for four different scans (colored) for W1, W2, W3, W4 (left - right). | |||

The frame-mask product (frameID-wBAND-msk-1b.fits) and bit-definitions therein were described in section i.2. This mask is initialized in the ICal pipeline by first copying all information from the static calibration mask into the first 8 bits of a 32-bit buffer (see Table 2). Next, we set the dynamic bits: 9 - 18 according to specific values in the input raw L0 frame. These were assigned on-board the spacecraft during Sample-Up-the-Ramp (SUR) processing (section ii.). L0 pixel values of 32,752 + n, where n=1...9 are reserved to encode the SUR number where a ramp begins to saturate after A/D conversion. n=1 corresponds to the first sample read and means the entire ramp is saturated. This is usually referred to as "hard" saturation. The L0 values 32,752...32,761 are therefore assigned to the 9 saturation bits: 10...18 respectively. As a detail, hard saturation for W1 and W2 will occur at n=2 since the first sample for these bands is unreliable and excluded from on-board SUR processing (therefore, bit 10 is never set for W1,W2). Hard saturation for W3 and W4 will occur at n=1. Furthermore, the special L0 value 32,767 is assigned to bit 9 and usually means that the on-board SUR processing yielded a negative slope measurement, e.g., due to a noise spike or glitch in the ramp.

Bit values in the frame mask products were defined in Table 2, with the first 8 bits copied from the static bad pixel calibration masks. The static bad pixel masks represent the population of pixels permanently masked from processing because they have the potential to compromise photometric accuracy and precision. Criteria for the rejection of pixels relate to the level at which any one of these phenomena has the potential to add to the uncertainty of or bias the flux for an extracted point source. Inputs to static bad pixel mask generation included:

Conditions that trigger the identification of a static bad pixel include:

Many of these conditions are inter-related. For example, pixels with significant dark current exhibit excessive Poisson noise in the fixed WISE exposure time and can be a readily rejected based on their noise behavior. Each of these conditions was evaluated independently from the others so that pixels could be rejected for multiple conditions and combined into a final static bad pixel mask for each band that encoded all of the rejection thresholds violated by any given pixel.

Bad pixel rejection criteria

Responsivity:

Flat fielding corrects for relative pixel response, even

if that response is significantly outside the median response of the

array. The static bad pixels masks reject pixels which

lie abnormally outside the distribution of pixel responsivity for a

given array.

These conditions are tagged as bits 2, 3, and 4 in the masks

(see Table 2).

Dark current and excessive noise:

Pixels can be flagged as

noisy because of intrinsic instability or due to Poisson noise from

excessive dark current. Pixels were identified for static masking due

to excessive noise if the RMS noise in a that pixel was three times

the median RMS noise for pixels across the array for W1 and W2 and two

times the RMS noise in W3 and W4. Pixels with three times the array

RMS would inflate the uncertainty of a faint source by 10% if the

source extraction footprint extends over 10 pixels. The static

bad pixel masks also account for pixels with abnormally low RMS

noise - those which lie below the main distribution - as was the case

for responsivity masking.

These conditions are tagged as bits 0 and 1 in the masks

(see Table 2).

Flat-field uncertainty:

Flat fields maps were derived from

backgrounds in on-sky data as described in section vii.

The resulting uncertainty maps for these flat fields were used to identify

statically masked pixels. Thresholds of 2% and 1% uncertainty in the

flat field were used from W1/W2 and W3/W4 respectively.

For lack of availability of additional bits, these conditions were

also tagged as bits 0 and 1 in the masks (see Table 2).

Table 4 provides the responsivity, RMS-noise, and flat-uncertainty thresholds for all bands. Also listed (last column) is the percentage of pixels masked using the criteria listed. This percentage excludes those masked for bad (non)-linearity and the ancillary conditions described below. Furthermore, these statistics only pertain to the active region of each array (10162 pixels for W1, W2, W3, and 5082 pixels for W4).

| Band | low response | high response | low rms

[DN] |

high rms

[DN] |

median rms

[DN] |

flat-uncertainty

[%] |

% rejected

(all criteria) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.5 | 1.11 | 2.4 | 8.7 | 3.9 | 2.0 | 1.77 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 8.1 | 3.7 | 2.0 | 1.79 |

| 3 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 12 | 30 | 15 | 1.0 | 0.33 |

| 4 | 0.85 | 1.08 | 6.0 | 14 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 0.69 |

Linearity:

Pixels with a bad

(non)-linearity calibration

were also included

in the static masks (not shown in Table 4).

Here, those pixels whose non-linearity

estimates

were abnormally high, highly uncertain, and/or

unreliable as determined from a bad fit

to their Sample-Up-the-Ramp (SUR) data were

tagged as bit 6 in the masks (Table 2).

The thresholds for each band were picked by

identifying outlying populations in pixel

histograms of the non-linearity coefficient, S/N

ratios of their estimates (typically < 2.0),

and χ2 values

falling above or below several times the

standard-deviation expected for the

number of degrees-of-freedom of a specific fit.

Ancillary:

Two other static bad-pixel conditions listed in

Table 2 are bit 5:

"saturated anywhere in ramp" and bit 7:

"broken pixel or negative SUR". These

occured in the input frame data used to generate the

calibration products and refer to respectively

instances where a pixel was saturated

(e.g., always excessively hot) or behaving erratically

in on-board SUR processing (see section iii.)

In closing, only a subset of the static bad-pixel conditions were used to "NaN-out" pixels in the level-1b intensity and uncertainty frame products. All conditions used for NaN'ing were summarized here (end of section i.2.). The static bad-pixel conditions considered fatal enough for NaN'ing are those defined by bits 0, 1, 2, 3, OR, 4 in Table 2, with threshold information summarized in Table 4. As mentioned above, these bits are not mutually exclusive, i.e., more than one of condition could apply to the same pixel. Those static conditions not used for NaN'ing merely serve as a warning.

Droop is a signature of the W3 and W4 arrays and manifests itself in two forms: (i) intra-quadrant splitting, usually bisecting a saturated source or region, and (ii) global quadrant-to-quadrant (Q-to-Q) effects leading to a depression of one or more quadrants followed by an increase (or rebound) in the quadrant signals in subsequent frames. During the rebound phase, the quadrants also become unstable at the location of bad-pixel clusters and the banding/split structure seen in the dark becomes apparent, lasting for 10-20 frames. These residual bands (in excess of those seen in the static dark calibration) are also referred to as "stationary splits" and were corrected using the same algorithm designed for intra-quadrant droop-splits. All forms of droop have been confirmed to be additive in nature and were corrected using relative in-frame offsets. There is also a final (optional) refinement step for cases where a global Q-to-Q correction could not be computed. We describe the algorithms (in order of execution) in sections iv.1, iv.2, and iv.3. Figure 1 (red boxes) shows the location of these steps in the pipeline flow. Section iv.4 summarizes anomalies and liens from the droop correction.

Here are the steps for correcting this flavor of droop.

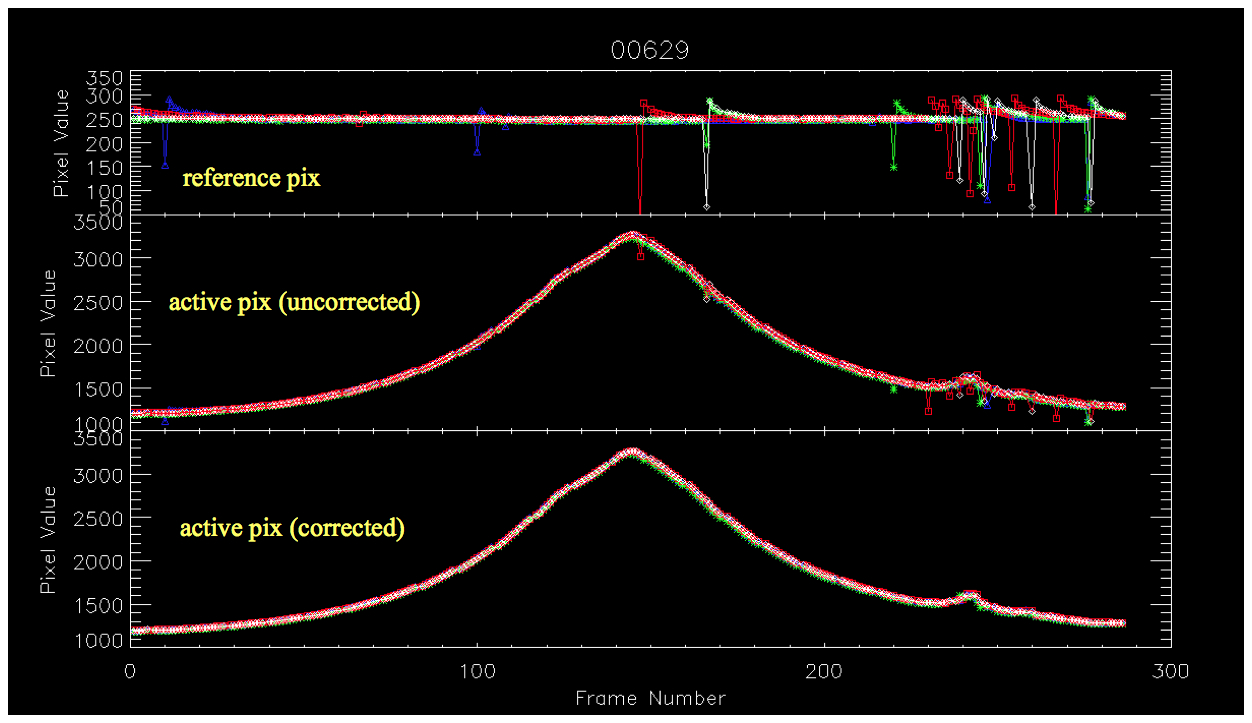

Following the intra-quadrant split corrections, quadrant-to-quadrant (Q-to-Q) relative offsets were then computed and applied to equalize levels over the whole frame. This step exclusively used the reference pixels where possible (which may have been updated by the split correction step above). The correction was computed for each separate quadrant by first computing the median of all its good reference pixels, where "good" meant pixel values < 32,767 (32,767 being the specially encoded L0 pixel value indicating a bad on-board estimate for the pixel signal - see section iii.). This median was only computed if the fraction of good pixlels in a reference region was > 0.9.

The median reference-pixel signal for each quadrant was then differenced with its long-term median signal to compute a relative offset correction. These long-run baselines (one for each quadrant in W3 and W4) were calibration inputs. These baselines were seen to be stable over long periods and appeared to represent the natural levels that the reference pixels returned to after a droop and/or rebound event (see Figure 7). The relative corrections were then applied to the active pixels of each respective quadrant. This brought them in line with what one would have observed if no droop or rebound event occurred.

If the fraction of good reference pixels was <= 0.9 for any quadrant, no correction was applied to the active pixels. Instead, a flag was set and propagated downstream to the optional droop-refinement step (see below).

|

| Figure 7 - Trend of reference pixel medians (top), corresponding active pixel medians before the Q-to-Q correction (middle), and after correction bottom) for all frames in a scan. |

If a global correction using reference pixels alone (section iv.2.) could not be computed for a quadrant, e.g., because there were an insufficient number of good reference pixels, we attempted to compute an offset using the active pixels in neighboring quadrants where a droop-correction was possible. In order to minimize biases from quadrant-dependent instrumental residuals, this step was performed after all instrumental calibrations were applied.

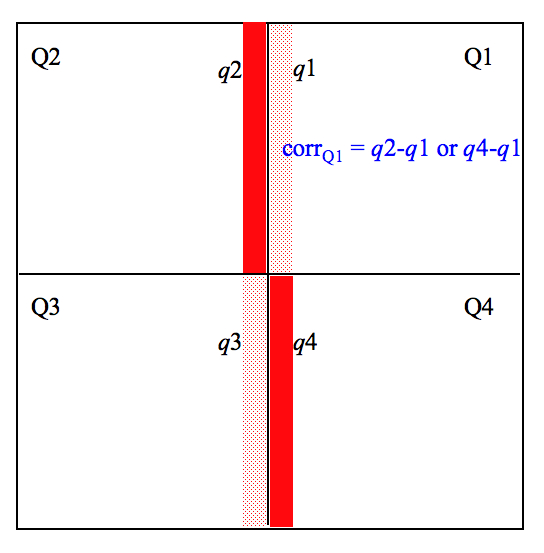

We first computed lower-tail quantile values in strips of width 50 pixels for W3 and 25 pixels for W4 running up and down the center the frame. Figure 8 shows an example of a correction for quadrant Q1. The correction for this quadrant used the strips colored solid red. If a Q-to-Q droop correction using reference pixels alone was possible for Q2, the offset correction for Q1 was obtained from the quantile difference: quant(Q2) - quant(Q1). This correction was added to all the active pixels of Q1. If a correction was not possible for Q2, we looked at the bottom quadrant, Q4, and used the active pixels in its strip to compute the offset correction for Q1, i.e., quant(Q4) - quant(Q1). The same procedure was used for the other quadrants that failed to be corrected for global Q-to-Q droop (section iv.2.). E.g., for Q3, the correction sought for was first quant(Q4) - quant(Q3), but if Q3 was not initially corrected for Q-to-Q droop, we tried using quant(Q2) - quant(Q3) instead.

If no correction was possible after two attempts at using the

neighboring "good" quadrants, we gave up and left it at that. Note that we avoided using

strips aligned in the horizontal direction (above/below the quadrants) due to the

possibility of badly corrected splits, either from droop or residual banding.

This would have biased the active-pixel corrections.

|

| Figure 8 - Schematic for final droop refinement if the reference pixel method for correcting Q-to-Q droop (section iv.2.) for any quadrant could not be used. |

Figure 9 shows a collection of raw (level-0) W3 frames containing

"drooped" and droop-induced split quadrants. The calibrated and droop-corrected

(level-1b) frames are shown on the right.

|

|

| Figure 9 - Left: Raw (level-0) W3 frames and Right: same frames after droop corrections and other calibrations were applied. Pink regions are NaN'd bad pixels. | |

As mentioned in the cautionary notes section (I.4.d), droop corrections were not always accurate. Residuals are sometimes seen in preliminary-release W3 and W4 level-1b products. These will be mitigated for the most part in the final release. There are three anomalies one should be aware of. The last of these (#3) is a lien and is not removed in final-release level-1b products.

W1 and W2 darks were generated by stacking ~46,000 cover-on (dark)

frames acquired during the In-Orbit Checkout (IOC) period.

The stacking used a trimmed averaging method.

The dark levels in the calibrations are generally below 1 DN and the 1-σ

uncertainty per pixel

was of order 0.013 DN for both bands.

Figures 10 and 11 compare the

flight-derived (IOC) dark calibrations (right) with

those derived several months earlier on the ground (left), for W1 and W2

respectively.

The major difference is an increase in the number of bad pixels in flight,

by ~60% in both bands.

This degradation

is expected to be due to repeated thermal cyclying of the arrays

during testing prior to flight.

Nonetheless, the fraction of bad pixels in the W1, W2 arrays

was still relatively low and under ~2%

(see section iii.1. for a summary of

bad pixel statistics).

|

| Figure 10 - Dark calibration images for W1. Left: from laboratory (MIC2 testing); Right: from cover-on flight data. Pixel signals are at same stretch. |

|

| Figure 11 - Dark calibration images for W2. Left: from laboratory (MIC2 testing); Right: from cover-on flight data. Pixel signals are at same stretch. |

Band 3 and 4 darks

Unlike W1 and W2, the cover was too warm to permit the measurement of dark images for W3 and W4 during IOC. The W3 and W4 arrays were de-biased to minimize degradation during this period. The ground darks were unsuitable for preliminary processing since the on-orbit frames exhibited residual bias structure after the calibrations were applied. This could be due to the different electronics used in ground testing and in flight. We therefore proceeded to estimate darks using illuminated frames from the regular survey. The procedure used ancillary products generated from the responsivity (flatfield) calibration step (section vii.). This is outlined below.

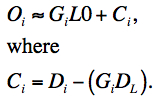

First, we assumed a simple model for the signal observed in detector pixel i:

|

(Eq. 3) |

A proxy for the "true" sky signal Si is taken to be the median raw-frame (L0) signal over all array pixels minus some (unknown) absolute dark level DL, i.e.,

|

(Eq. 4) |

The observation model in Eq. 3 then becomes:

|

(Eq. 5) |

The flat (slope) Gi and intercept Ci were initially estimated by fitting the first line of Eq. 5 to each L0 pixel using the change in the zodiacal background as determined by the median L0 level. This was provided by the responsivity (flatfield) calibration step described in section vii.. The dark signal per-pixel was then derived from:

|

(Eq. 6) |

We assumed values of the absolute dark level DL from ground testing. Regardless of the absolute level, what's important here is that the underlying dark variation (and banding structure) was captured.

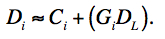

The above method was initially used to derive provisional darks for use in initial processing. However, when more survey data became available, a new set calibrations were generated to support processing for the preliminary release. In this new round, the flatfield products were not generated using L0 frames as inputs, as above, but were generated from dark-subtracted (using provisional darks) and linearized frames. Therefore, instead of fitting to background variations in L0 frames directly, we fitted to the linearized pixels Li versus their median level L. The latter then became a proxy for the change in overall sky signal Si ~ L, similar to Eq. 3:

|

(Eq. 7) |

Given the input data had been dark-subtracted using the old dark, the intercept ΔDi from this new fit was the correction needed to derive the new dark from the old (provisional) dark:

|

(Eq. 8) |

The new W3, W4 darks used in processing for the preliminary release are shown on the right in Figures 12 and 13 respectively. For comparison, we also show the darks derived from ground testing. Even though qualitatively similar, significant differences are indeed present. The flight-derived darks vastly reduced the instrumental banding structure when applied, and the impact was most noticeable in the quality of coadded image products. An overall assessment of the residual bias variations in frame products is given in section x.1.

In closing, we mention that the darks for all bands include

the constant offset term O/2T that is

added to all frames during on-board Sample-Up-the-Ramp processing

(see Eq. 1 in section ii.).

Therefore, this offset is automatically removed from frames

after dark subtraction. The pixel values then become proportional

to the photon accumulation rate.

|

| Figure 12 - Dark calibration images for W3. Left: from laboratory (MIC2 testing); Right: from flight data using the method described above. |

|

| Figure 13 - Dark calibration images for W4. Left: from laboratory (MIC2 testing); Right: from flight data using the method described above. |

The non-linearity calibration was derived from ground test data on a per-pixel basis and then validated using an on-orbit experiment. Overall, we were able to adequately linearize each array up to its saturation level as defined by the maximum signal after A/D conversion. These saturation levels were at typically ~85-90% full well across all bands. At these levels, the accuracy of the linearity calibration as determined from random statistical uncertainties and repeatability analyses of the laboratory data is ~0.31, 0.33, 0.24, and 0.62% for W1, W2, W3, and W4 respectively. Note that this ignores any possible systematic errors associated with for example how representative the laboratory measurements were of the actual flight data. Characterization of the non-linearity from flight data has proved difficult and only coarse checks with photometry at similar wavelengths from other instruments were possible. We first outline the method and summarize some results. Validation checks using color-magnitude diagnostics from source photometry are presented in section vi.1.

Initial analyses of Sample-Up-the-Ramp (SUR) test data for a few pixels (e.g., Figure 14) revealed that a quadratic correction model was sufficient. The method was based on fitting the SUR test data with the following model:

|

(Eq. 9) |

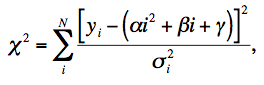

Note that the ramp intercept γ played no role in determining the ramp shape. It was simply carried along to absorb dependencies that could not be explained by α and β. The parameters α and β were estimated by fitting Eq. 9 to the ramp data yi for each pixel using χ2 minimization. The following quantity was minimized:

|

(Eq. 10) |

where σi are estimates of the uncertainties, taken as the RMS deviation in repeated exposures at each ramp sample. N was the total number of data points in the fit and included multiple ramps from repeated exposures at the same illumination. Since Eq. 9 is linear in the fit coefficients, the values of α and β that minimize χ2 could be written in closed form. This is a standard textbook result and explicit solutions are not given here.

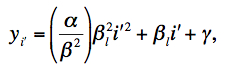

Given that Eq. 9 was fit to a specific set of laboratory data, we can generalize to any other observed ramp with underlying linear count rate βl by scaling the "time" i at which the linear counts are equal, i.e., if βi = βli' at times i and i', then i = βli'/β. We can then transform Eq. 9 into a new generic expression for the counts in a ramp with linear rate βl:

|

(Eq. 11) |

The assumption of this method should now be apparent: the quantity α/β2 is assumed to be constant and independent of the incident flux. The parameter α is < 0 since the non-linear ramps generally curve downwards. This means that the fractional loss in measured counts at any ramp sample i from the linear expectation is ~ (α/β2)βli. A higher incident flux will therefore suffer a proportionally greater loss at all ramp samples.

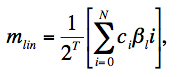

A linear output signal (i.e., assuming the detector was perfectly linear) can be written in terms of the true linear ramp count (βli) and the SUR coefficients using Eq. 1 in section ii.:

|

(Eq. 12) |

where it is assumed that a dark (and the offset term O/2T) have been removed. On re-arranging, the true linear rate can be written in terms of the linear signal as follows:

|

(Eq. 13) |

Substituting Eq. 13 into Eq. 11, we obtain:

|

(Eq. 14) |

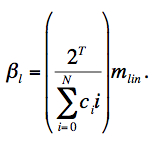

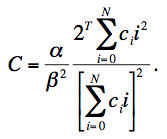

Substituting Eq. 14 into Eq. 1 from section ii. and rearranging terms, the observed signal mobs for a pixel can be written in terms of its linearized counterpart mlin after subtraction of the offset term O/2T as follows:

|

(Eq. 15) |

where

|

(Eq. 16) |

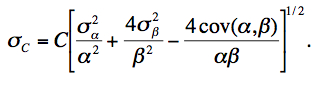

Generally we expect C ≤ 0 with C = 0 implying a perfectly linear detector. The quantity C in Eq. 16 is defined as the non-linearity coefficient and is provided (along with its uncertainty) as a FITS image for use in the ICal pipeline. The 1-σ uncertainty in C uses the error-covariance matrix of the fit coefficients and is given by:

|

(Eq. 17) |

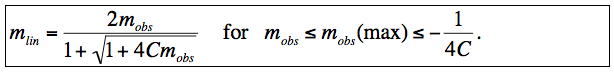

Eq. 15 can be inverted to solve for the linearized signal mlin:

|

(Eq. 18) |

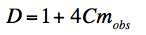

The quantity in the square root is the discriminant:

|

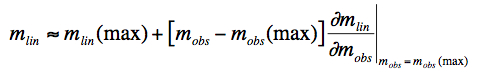

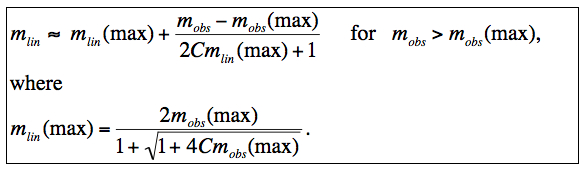

and we require D ≥ 0 for a physical solution. This implies there is a maximum observed signal: mobs = -1/(4C) above which a measurement cannot be linearized and hence could not have come from a detector with this model. It is very possible that the observed signal predicted by Eq. 15 turns-over before the maximum of the dynamic range is reached: 32752. Signals satisfying -1/(4C) < mobs ≤ 32752 therefore cannot be linearized using this model. To avoid (or "soften" the impact of) a possible turn-over, we define the quadratic model solution in Eq. 18 to be only applicable to observed signals mobs ≤ mobs(max), where mobs(max) is a new calibration parameter. For mobs > mobs(max), we Taylor expand Eq. 18 about mobs = mobs(max) to first order and linearly extrapolate to estimate the linearized signal:

|

(Eq. 19) |

Using Equations 15 and 18, the linearized signal for observed signals mobs > mobs(max) can be written:

|

(Eq. 20) |

This extends the flexibility of the quadratic model and is important for characterizing the non-linearity at high signals where its effect is most extreme and there is no guarantee that it follows a simple quadratic.

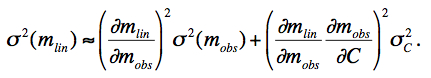

The 1-σ uncertainty in the linearized pixel signal can be derived by Taylor expanding Eq. 18 about mlin to first order, squaring, and taking expectation values to derive the variance:

|

(Eq. 21) |

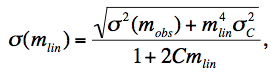

Evaluating the derivatives, the uncertainty in the linearized signal can be written:

|

(Eq. 22) |

where σC was defined by Eq. 17. If the discriminant (D) in Eq. 18 is < 0, we reset D = 0 so that mlin = 2mobs from Eq. 18. In this limit, the uncertainty in linearized signal becomes σ(mlin) = 2σ(mobs).

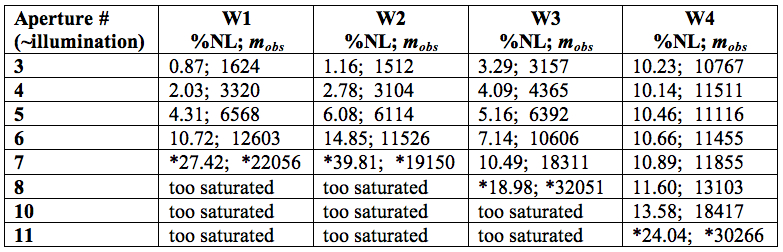

Table 4 summarizes the measured

deviation from linearity

using the laboratory characterization. Some notes follow below the table.

W2 appears to be the most "non-linear" band at signal levels above

~10,000 DN (~70% full well). Figure 14

shows some example SUR data

for a single "well behaved" pixel in each array for signal levels

reaching ~55, 60, 60, 60% full well for W1, W2, W3, W4 respectively.

Table 4 - Deviations from linearity (median % over all frame pixels)

at

selected median signal levels (mobs).

|

Figure 15 shows images of the actual

non-linearity coefficient C (Eq. 16) for all bands, all

on the same color scale.

Note that the range of values map into the inverse of the size

of the non-linearity, i.e., the darkest regions correspond

to greatest non-linearity. Hence, W2 is the most non-linear overall.

There is also a significant spatial variation in the magnitude of the

non-linearity in each array, therefore justifying our

per-pixel characterization, instead of one calibration

coefficient per array.

Also, there is a general tendency for pixels to be more

non-linear towards the center of the W1, W2 arrays. This

is reversed for W3, W4 where pixels near

the edges are relatively more non-linear (by ~10%).

Figure 16 shows examples of ramps constructed

using several photometric calibrators (with known brightness) for

W1 and W2.

The black curves are predictions from the non-linearity models

presented in section iv.,

where the median calibration

coefficient (e.g., Figure 15)

over all array pixels was adopted.

There is good qualitative agreement between the models and the data

for these bands.

A similar analysis for W3 and W4 was difficult due to the paucity

of bright enough photometric standards that fell within

the spatial domain of the experiment.

As a further check, we constructed color-magnitude diagrams (CMDs) involving 2MASS and all WISE bands for A0 dwarf stars from the Michigan Spectral Atlas (Figure 17.) The WISE photometry was from multiframe processing for the preliminary release and drawn from the internal working source database. Sources at galactic latitudes |b| > 20o are shown as green points. Overall, even though the scatter is large, there does not appear to be a significant tilt in the color locus towards bright magnitudes for W1, W3 and W4 that may point to an over- or under-correction of flux in the WISE bands from an erroneous linearity calibration. For W2, the extreme curvature seen in Ks - W2 towards bright magnitudes is not expected from the intrinsic color distribution of this population. The departure starts at approximately where saturation sets in and we have verified that it is not due to an erroneous linearity calibration. It points to an unforeseen feature of the W2 array whereby the PSF becomes flux dependent at bright magnitudes. This was documented in the cautionary notes section (I.4.b).

|

|

|

|

| Figure 17 - Color-magnitude diagrams involving the 2MASS Ks band and WISE bands: W1, W2 - top; W3, W4 - bottom, for A0 dwarfs from the Michigan Spectral Atlas. Black points are all matches and green points are for |b| > 20o. The vertical red lines at zero color are to guide the eye. Note, the extreme deviation at bright magnitudes for W2 was discussed in section vi.1. | |

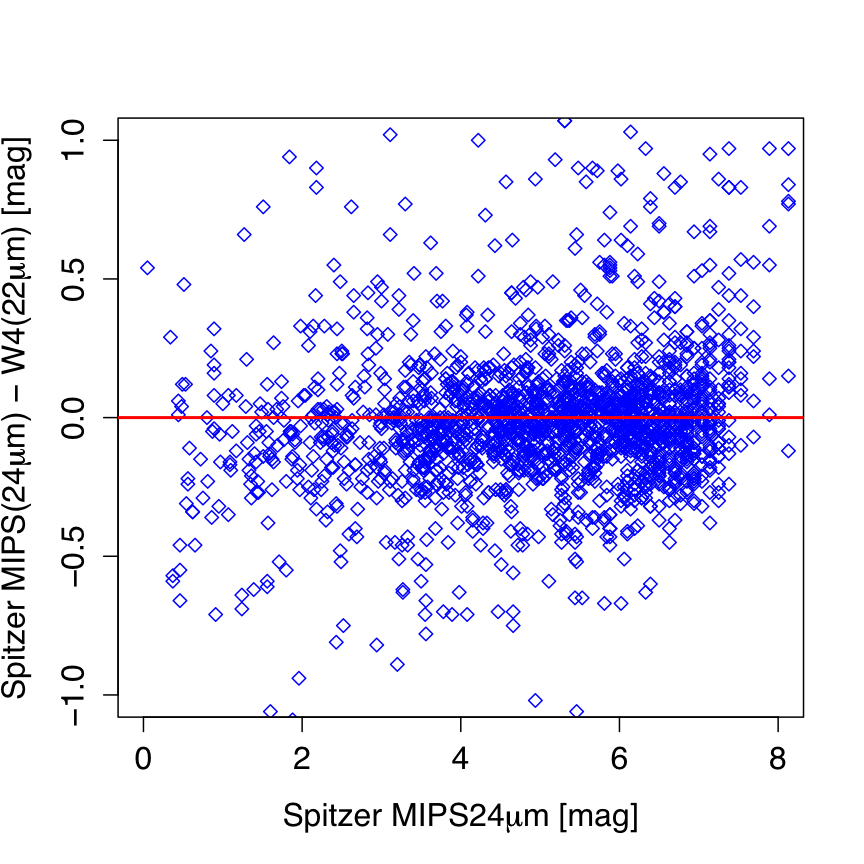

Lastly, Figure 18 compares photometry in W4 with

Spitzer-MIPS24μm for a sample of Young Stellar Objects.

Even though the scatter is large and statistics small at bright magnitudes

(note: W4 enters saturation at ≈ -0.6 mag),

there does not appear to be

a significant deviation between these two photometric

systems that may point to an erroneous linearity correction in W4.

|

| Figure 18 - Magnitude difference using Spitzer MIPS24μm band and W4 (22μm) versus MIPS24μm magnitude for a sample of Young Stellar Objects. Red line is to guide the eye. |

Flat-field calibration images for all bands were created directly from the on-orbit survey data. No separate dedicated data were acquired on orbit for the flat-field calibration. Below we describe the methods used. The relative flat-fielding accuracy achieved in each band is summarized in section vii.2.

In order to check the stability of the flat-field during the cryogenic mission, one flat-field image was created from each month of data in the cryogenic mission. It was determined that all observed variations between these flat-field images were due to the changing illumination pattern of the Galactic background, and not a time-varying pixel response. Hence, for the final release, a single static master flat-field will be created for each WISE band utilizing all of the data from the cryogenic mission. For the preliminary release, the processing schedule only allowed for the use of images from early in the mission, specifically, images obtained in February of 2010.

Two different methods were employed to create the flat-field images for W1 & W2,

and W3 & W4, respectively. For W1 & W2, a frame-stacking method was

implemented as follows. A dark image was subtracted from each of the input frames, then each frame

was pre-normalized by its respective median pixel value. An outlier-trimmed average was computed for

each pixel stack and the resulting image was normalized by its median value to create

the normalized flat-field image. In addition,

a corresponding uncertainty image was created by dividing the trimmed stack standard-deviation

image by the square root of the stack-depth at each pixel. Approximately 28,000 input frames were used in the

creation of the flat-field images, excluding frames

at low Galactic latitudes and those impacted by the moon. The final flat-field and uncertainty images

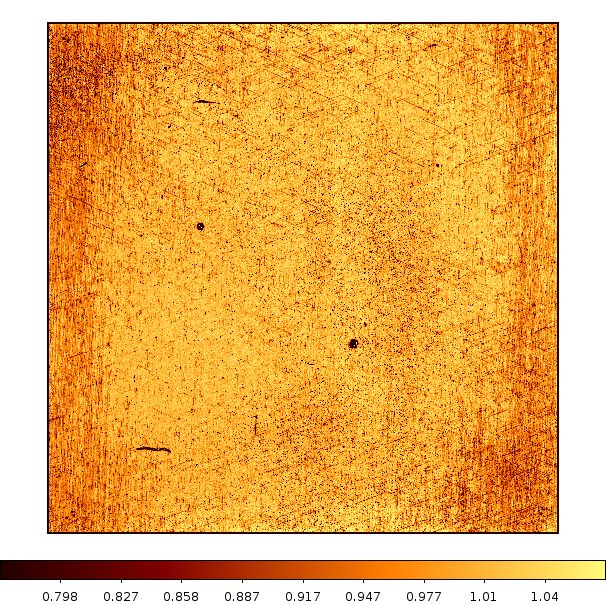

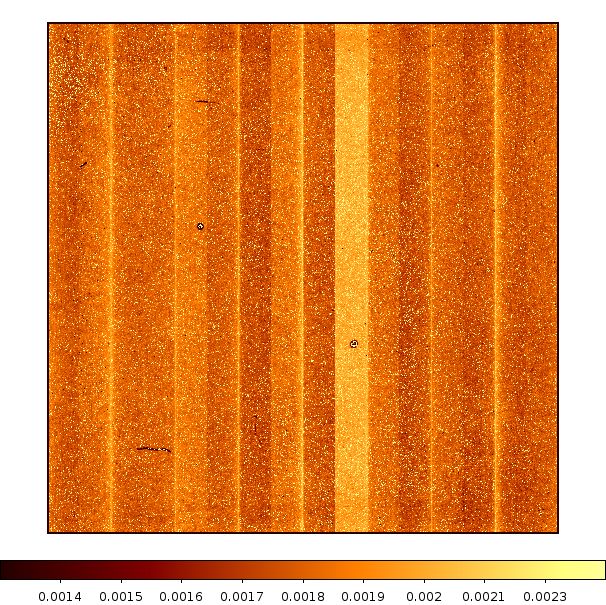

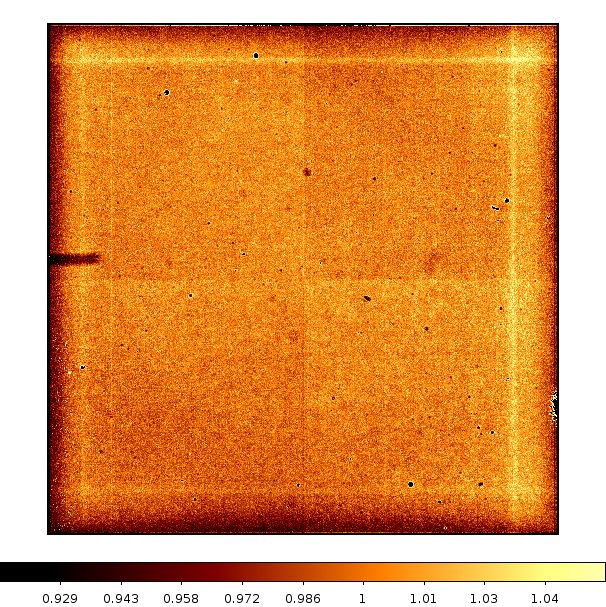

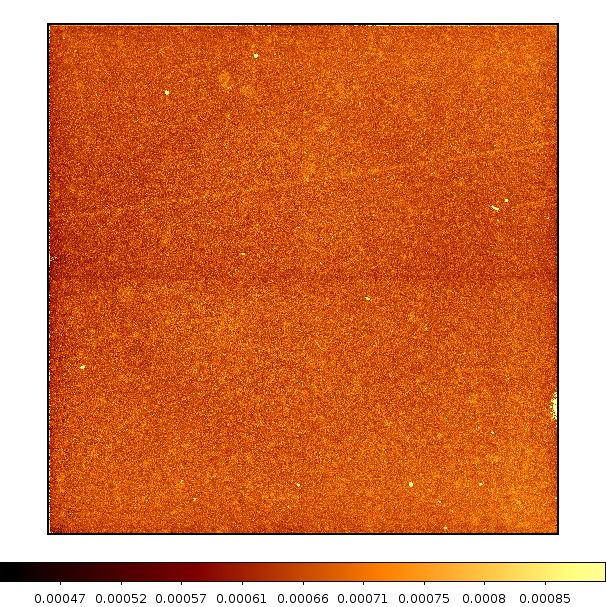

for W1 and W2 are displayed in Figures 19 and 20, respectively.

|

|

| Figure 19a - W1 Flat-field image | Figure 19b - W1 Flat-field uncertainty image |

|

|

| Figure 20a - W2 Flat-field image | Figure 20b - W2 Flat-field uncertainty image |

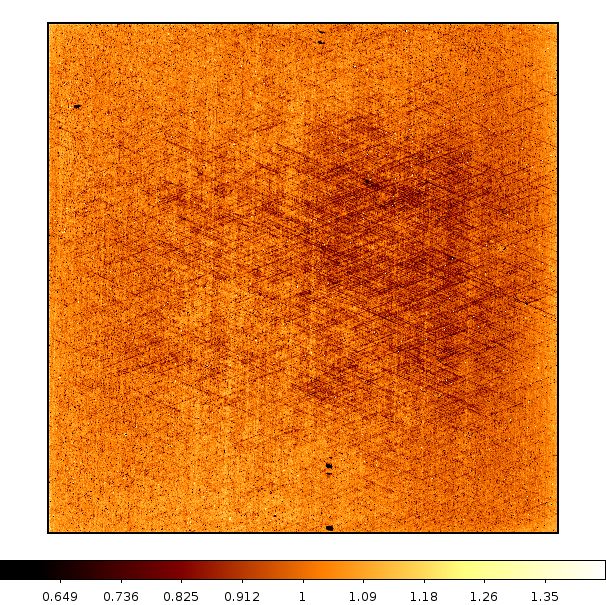

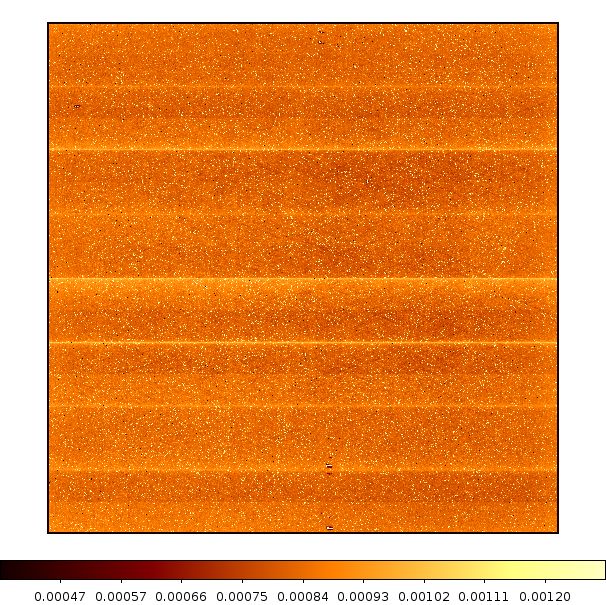

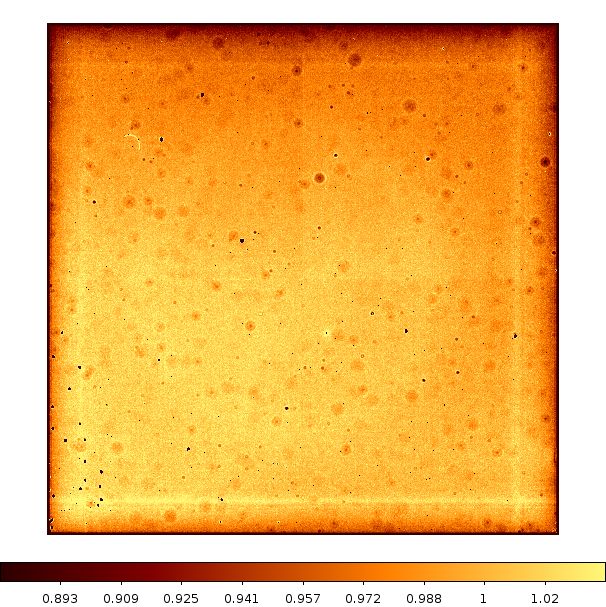

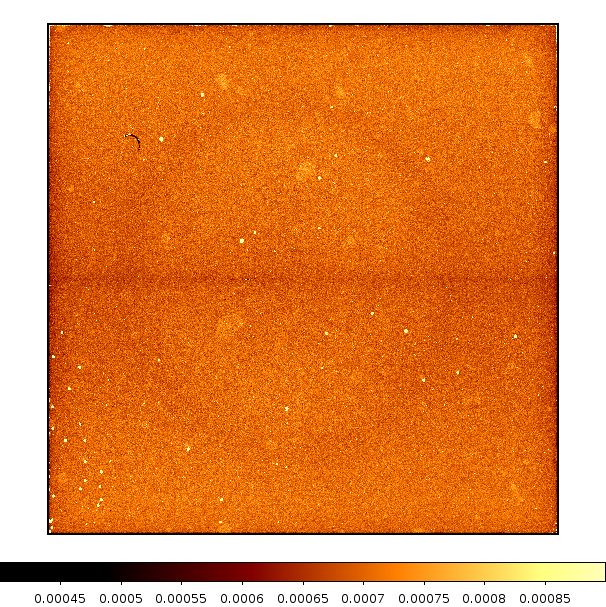

For W3 & W4, flat-field images were created by measuring the change in intensity in a pixel

in response to the variation in overall intensity on a frame as the uniform illumination on the

array from the zodiacal background varied. The relative responsivity for a pixel is given by the slope

of a linear fit to the pixel versus overall frame intensity. This "slope" method helps mitigate

incomplete knowledge of the static absolute dark/bias level. For W3 & W4, a more careful

selection of input frames was performed than for W1 & W2. Latent images of celestial sources

that persist on both short and long time scales were found to pose a particular challenge to creating

"clean" flat-field images. W3 & W4 were annealed about every 12 hours to periodically remove these

accumulating latents. However, since the responsivity itself changed

as a function of time since an anneal, we

compromised and selected frames relatively close to anneals in order to have as few

latents as possible, but not too close to be affected by the responsivity-altering behavior of the

anneal itself.

Like W1 & W2, frames at low Galactic latitudes and those affected by the moon

were excluded from the input list. Due to the tighter selection criteria, only about 4,000

frames were used for W3 & W4. The final flat-field and uncertainty images

for W3 & W4 are shown in Figures 21 and 22, respectively.

|

|

| Figure 21a - W3 Flat-field image | Figure 21b - W3 Flat-field uncertainty image |

|

|

| Figure 22a - W4 Flat-field image | Figure 22b - W4 Flat-field uncertainty image |

An estimate of the flat-field accuracy is provided by the relative percent uncertainty derived from the uncertainty images. This is defined as the median of 100 * [σ(f) / f] over all the pixels where σ(f) is the 1-sigma uncertainty in the responsivity f for a pixel. The median relative percent uncertainties for all WISE bands are listed in Table 5. Histograms of the relative uncertainty per pixel are shown in Figures 23 - 26.

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.18% | 0.08% | 0.07% | 0.07% |

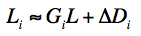

The purpose of dynamic calibration (dynacal) is to capture instrumental transients in the WISE detectors and then correct them in the frames from which the calibrations were made. The dynacal process is executed in parallel with ICal. Dynacal generates two products per frame: (i) a "sky-offset image" from a running median of N consecutive time-ordered frames along a scan, where the pixel values therein are renormalized to have zero median; (ii) a transient bad-pixel mask that stores new bad pixel information. "Bad" here refers to pixels whose values persist in a high or low state for several consecutive frames centered on the frame of interest. We discuss each in turn below.

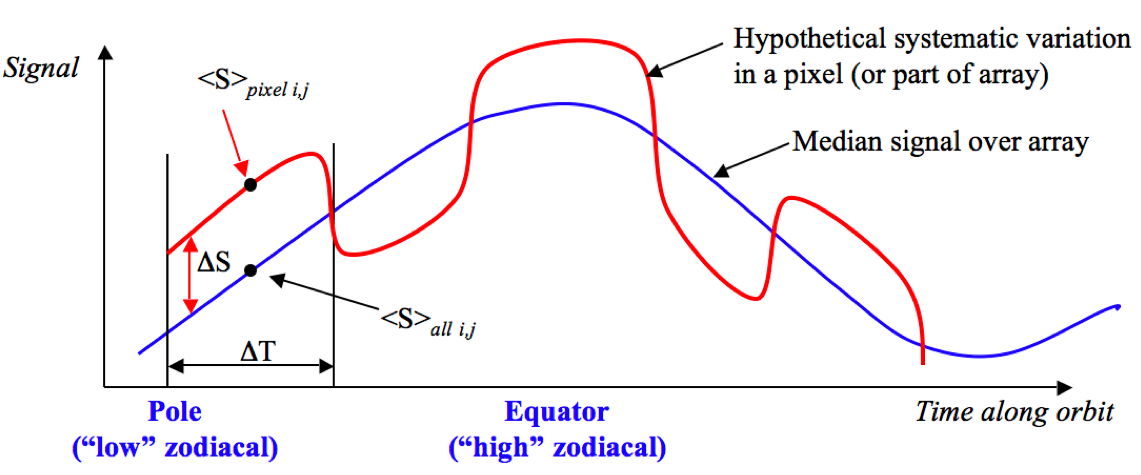

The goal of this correction is to capture short-term variations in the bias and dark structure that could not be corrected by the static long-term calibrations. Possible short-term variations were mitigated by median-stacking ~40 frames per band (after filtering of bad frames) within a moving window along the WISE orbit to create a "sky" image, removing the global pixel median (to create the "sky-offset" image), and then subtracting this from the frames. Note that we needed to stack ~ 30-40 frames per window to reliably filter out sources in any band. This number therefore became the characteristic time scale: 40 x 11 sec/frame ~ 7 min (or ~ 7.7% of a WISE orbit) on which to capture any instrumental variations. A one-dimensional schematic of the sky-offset cencept is given in Figure 27.

As a detail for the preliminary release, the sky-offsets were made using a moving window with a step-size of ~10-15 frames between windows. The exact number varied according to how each scan was partitioned into windows since the number of frames per orbit, as well as after filtering, varied slightly. This was mainly done to reduce processing time. Processing for the final release will use a single frame-step moving median.

Input frames for the dynacal pipeline (both for sky-offset creation

and transient bad pixel tracking - see below) were first pre-calibrated

through an initial pass of ICal. They were mainly dark-subtracted, linearized,

and flat-fielded (see

Figure 1). Flattened frames were then fed into the

dynacal pipeline to create all

calibrations on a per-scan basis. These were then

applied to the respective

windowed-frames in a subsequent run of ICal. An uncertainty image for each

sky-offset was also generated

(derived from a robust stack RMS)

and propagated along.

|

| Figure 27 - One-dimensional schematic illustrating the concept of the sky-offset calibration. Symbols are defined below. |

Labels and symbols in Figure 27:

A study of the benefits and impacts of the sky-offset correction on the final photometric accuracy is yet to be performed. However, we mention that the sky-offset calibration had a huge benefit for W3 and W4. This was mainly in mitigating long-term image persistence (or latents) in these bands (described under section IV.3.f.iii). Latent tracking was not the original intent of dynacal, but there was a class of latents that persisted long enough (until the next anneal) to be captured and partially removed on a per-frame basis. These latents were also caught by our transient bad-pixel detector (see section viii.2.), and tagged as bit #21 in the frame masks.

Figure 28 shows a blink animation of a frame processed with and without a dynamic sky-offset correction. The long-term latents appear as fuzzy entended blotches in the uncorrected frame. As mentioned above, these long-term latents were sometimes only partially removed. This is because the sky-offset correction is purely additive, while the long-term latent phenomenon is a multiplicative effect associated with changes in detector responsivity. Residuals from incomplete "subtraction" of latent artifacts are often seen in single exposure products from the preliminary release (see image anomalies under section II.4.a.ii). The dynacal pipeline has since been updated to include a dynamic responsivity (flatfield) correction to help remove these long-term latent signatures from final release products.

|

| Figure 28 - Click for a blink-animation of a W3 frame containing long-term latents and same frame corrected using a dynamic sky-offset calibration. |

Transient bad-pixel masking attempts to tag pixels which become hot or unresponsive for a period of time, or remain so for the duration of the mission. The static bad-pixel masks (section iii.1.) only record those pixels which are known to be "bad" a apriori from analysis of all static calibrations (Table 1). Our transient detection method still has limitations, e.g., it is only sensitive to high and low pixel excursions from normality, and only if they stay this way for a consecutive run of 9 frames (for the preliminary release). Pixels which become noisy and start to fluctuate wildly on shorter timescales will escape detection.

The method uses the fact that bad pixels are always at the same x, y location in a set of frames, whereas astronomical sources move around as the frames are dithered or systematically offset from each other on the sky. Therefore, if a pixel is detected as an outlier with respect to its neighbors in a given frame, and it persists in this state (as an outlier) for the next consecutive N frames, it can be identified and tagged. The spatial outlier-detection is performed by first subtracting a smooth varying background from a frame, robustly-estimated over a 8 x 8 grid (all bands), and then applying robust statistics to the pixel distribution in each grid square to find outliers. This was repeated for the next N frames (in time-order). If the same outliers occured at the same x, y position for N ≥ 9 frames, the pixels were tagged with bit #21 in all N corresponding frame masks.

Note that since this method tagged all outlying pixels that remained fixed at their x, y position, it also tagged long-term image persistence artifacts (or latents - see section IV.3.f.iii). A further processing detail (that was done only for the preliminary release) is that pixels detected as transient were further disseminated to isolate those that showed a significantly decaying trend in their signal, e.g., as may be displayed by a short-term latent. These pixels were tagged with bit #25 in the frame masks. Given the probabilistic nature of this latent tracking method, it should not be relied upon in the preliminary release. We recommend you use the functionality developed in the ARTID processing system. This tagged latents and real sources contaminated by latents directly in the source catalog.

This step is "orthogonal" to (and complements) the temporal (frame-stack) outlier detection method described in section IV.5.a.v. The spatial-outlier detection method in ICal operates on a single frame basis and is designed to catch and tag (in the accompanying frame mask) abnormally high/low pixel spikes, and small "hard"-edged pixel clusters. This step is performed after all instrumental calibrations have been applied, but before selected bad pixels are replaced with NaNs in the final frame.

There are two

input parameters controlling the detection of hard-edged pixels:

(i) a threshold, trat, for

the ratio:

R = "regularized

pixel value / local median

filtered value at pixel location",

and (ii)

a linear kernel size n

(where n ≥ 3 pixels) specifying the size of the

n x n median filter.

If R exceeds trat,

the pixel is declared an outlier and tagged as bit #28 in the

frame mask;

The regularized pixel value in R is defined as abs(input pixel value - background) + 1, where abs is a function returning the absolute value of the argument. The background is estimated by computing medians within squares over a 10 x 10 grid on the frame. This block-median image is subtracted from the input frame and a constant of 1 is added. This constant is to avoid inadvertent division by zero when the background-subtracted frame is divided by the local median filtered image. The local median filtered image is computed using a 5 x 5 kernel. This operation replaces each pixel by a median of its neighbors and itself. The threshold for R and median-filter kernel size were tuned such that pixels with soft-edges were avoided, i.e., with neighbors whose signal declined no faster than that represented by a critically sampled PSF characteristic of the WISE bands.

Note that the threshold for detecting single-frame spatial outliers was inadvertently set too low for W1 and W2 in preliminary processing. This tagged the peaks of many "real" point sources in the frame masks. We therefore advise not using bit 28 for W1 and W2 from the frame masks. W1, W2 pixels tagged with this bit were not omitted from co-addition. No problem exists for W3 and W4.

In this section, we present some analysis to assess the accuracy of the calibrations in removing instrumental residuals from level-1b frame products in the preliminary release in general. We used two methods: (i) examined the magnitude and variation of spatial residuals by collapsing background-normalized frames along their column or row directions and stacking the results from thousands of frames, and (ii) explored the spatial variation in residual relative throughput across each array using relative source photometry of a large number of sources. Therefore, method (i) explored residuals in bias and dark structure, while (ii) explored residuals in the relative responsivity structure (or flatfield).

In summary, residuals in the bias structure are at a level of <~ 1%, 0.12%, 0.07%, and 0.07% for W1, W2, W3, and W4 respectively. These estimates use the maximum residual values from the analysis in section x.1 divided by the lowest background signals observed (conservatively speaking), which typically occur at the ecliptic poles. The residual biases in W1 and W2 are dominated by high-spatial frequency structure associated with the edges of amplifier channels. These will be mitigated in reprocessing for the final release. Residuals in the relative responsivity (section x.2) are at a level of ~ 2.1%, 1.6%, 3%, and 3.8% for W1, W2, W3, and W4 respectively. The W1, W2 estimates are peak-to-peak measures while the W3, W4 estimates are based on the 95 inter-percentile range. Even though these don't violate mission requirements, it is uncertain at the time of writing whether surface brightness variations induced by field-of-view distortion are having a significant impact on the residuals seen here.

To quantify the effectiveness of the instrumental calibration steps in removing systematic structure over many frames, residual plots were generated using a "Supermedian" stacking method. These Supermedians are plots of the median of the median-collapsed pixel values along the row or column direction from a large number of "calibrated" level-1b frames. They are useful to visualize residual spatial variations that occur along the row or column-pixel direction in general. For W1 and W2, the median of the entire frame is subtracted from each row or column median so the values are robust against sky-background variations. For W3 and W4, the same is done for each individual quadrant instead of the entire array. The RMS of the supermedian value is also computed, which gives a measure of the sensitivity and noise of each row or column.

For W1 and W2, data from ~13,000 frames in the scan range 02381b - 02437b were used. Frames with an array median of ≥ 4000 DN were ignored to avoid regions of high nebulosity, moon artifacts, and the galactic plane, which could skew the results.

Figure 29 shows the Supermedian analysis for W1. The top panel shows the residual signal in DN for each row of the array (the cross-amplifier channel direction). There is little variation seen. The second panel down in Figure 29 shows the RMS of the medians of each row. The array is slightly more stable towards the center with the RMS ≈ 8% higher at the edges. The third panel down shows the in-channel (column) residuals. There are 0.10 DN residuals in some columns. Two amplifier channels stand out as particularly noisy. The bottom panel shows the RMS of the in-channel residuals. Amplifier channels 10 and 14 are particularly noisy, and the inter-channel noise is quite evident in both the RMS and residual plots. The final WISE release will include corrections for these noisy channels.

The same analysis was also done for W2, shown in Figure 30. The plots used the same frame numbers as Figure 29. The top two plots show the residuals and RMS for for the cross-channel (column) medians, respectively. The residuals are generally less than 0.02 DN. The bottom two plots show the analysis in the in-channel direction. The residual amplitude is quite small, and the inter-channel noise is easily seen in the RMS plot.

For W3 and W4, approximately 20,000 frames were used in the scan range 01520a - 01689b. Row/column medians ≥ 2000 DN were ignored, so that frames with complex astrophysical structure or acquired shortly after an anneal do not skew the results.

The analysis for W3 is shown in Figure 31. Here, the medians were computed for each quadrant, and only for columns, as the majority of the droop-related corrections are applied by columns and not rows. The 4 panels show the results for each of the 4 quadrants. The black line and left axis are the residuals in DN, while the red line and axis are the corresponding RMS. Interestingly, the RMS dips in the middle of each quadrant, thus the array seems to be more stable (hence "more sensitive") at the center of each quadrant than at the center of the full array. The residuals are less than 0.3 DN for quadrants 1-3, but can reach 0.6 DN in quadrant 4. The abrupt jumps in the RMS and residual lines are due to the banding pattern seen in the W3 dark.

Figure 32 presents the same analysis for W4. Residuals are generally less than 0.2 DN. The RMS plots show a slight dip in the middle of each quadrant, and the RMS is generally higher at the array edges than at the center. There is slight roll-down seen in the residuals at the outter edge of each quadrant, but is only approximately 0.1 DN in amplitude.

Overall, the residuals measured here were too small to warrant a correction. The instrumental calibrations have generally kept the residuals below 0.3 DN. W3 has the highest residuals of any band (as high as 0.6 DN). The noise spikes and residuals seen in W1 and W2 will be mitigated in the final WISE data release.

We have used relative source photometry across each array to derive Low-Frequency (LF) responsivity maps. These quantify the relative spatial variation in throughput over the focal plane from the entire optical train. This will include surface brightness variations induced by distortion, i.e., from the non-uniform convergence and divergence of light rays, optical aberrations, and residuals from improperly characterized PSFs over the focal plane.

These maps complement the High-Frequency (HF) responsivity maps described in section vii., which mostly emphasize variations in the detector pixel-to-pixel gain. Some LF component may also be present in the HF maps. The LF maps emphasize power at spatial frequencies characteristic of the WISE beam convolved with a grid whose size is determined by the number of available photometric measurements. The LF maps are derived from profile-fit photometry off level-1b frames which have been corrected for detector gain variations using the HF maps. Therefore, the LF maps may also capture residual detector-gain variations not removed by the HF maps.

Here's an outline of the method:

We used ~30,000 frames processed for the preliminary release, within a radius of 14 degrees of the South Ecliptic Pole to maximize the number of frame overlaps. We performed the analysis for two different months in the mission: February and April 2010. There are no significant differences in the LF maps from these two periods. Results are shown in Figure 33 where the top row uses February 2010 data, and the bottom row uses April 2010 data. The qualitative agreement in the LF maps between the two months is reassuring. The accuracy of the relative responsivity maps is <~ 0.05% (S/N > 2000) in W1,W2, and <~ 0.23% (S/N > 400) in W3,W4.

Overall, the residuals in the relative responsivity from Figure 33 are at a level of ~ 2.1%, 1.6%, 3%, and 3.8% in W1, W2, W3, and W4 respectively. The W1, W2 estimates are peak-to-peak measures while the W3, W4 estimates are based on the 95 inter-percentile range of values. Even though these don't violate mission requirements, it is uncertain at the time of writing whether surface brightness variations induced by field-of-view distortion are having a significant impact on the residuals seen here. The low-frequency residuals may not be throughput related after all. The distortion-induced residuals are removed after correcting the frames for distortion during co-addition.

Last update: 2012 January 24